Recordings

$15

(includes s&h in the continental U.S.)

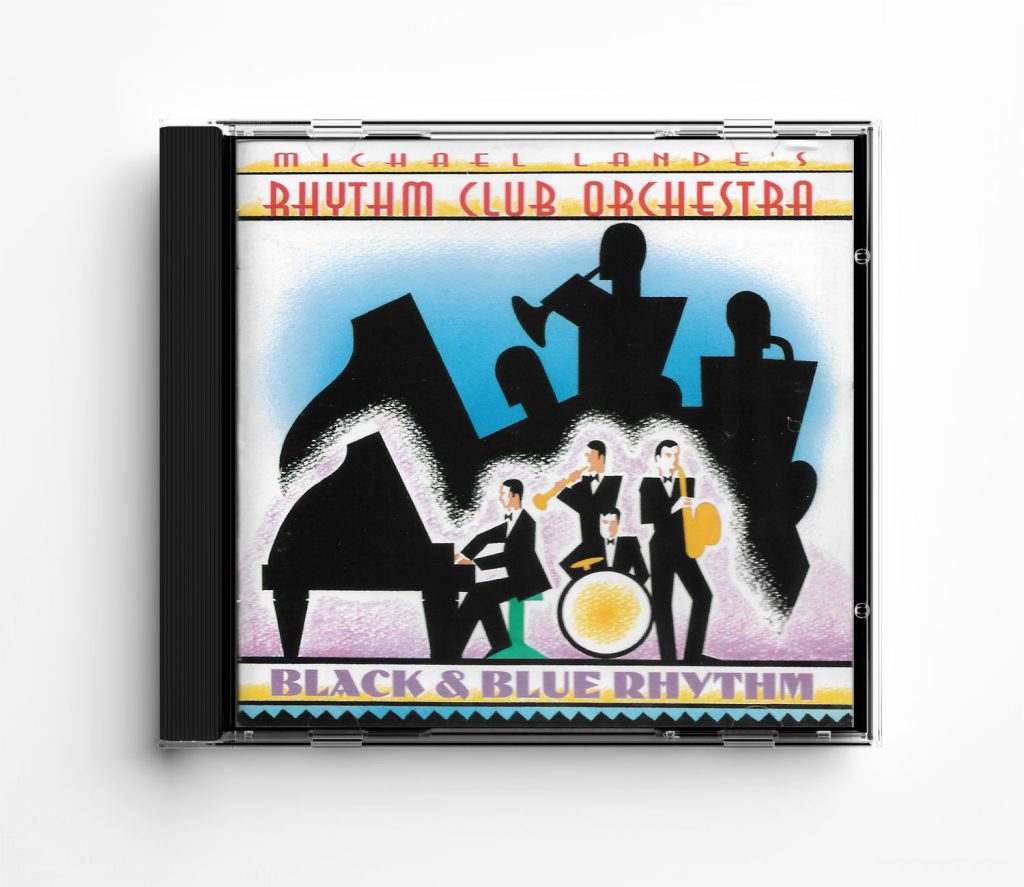

Black & Blue Rhythm

Michael Lande’s Rhythm Club Orchestra

The Rhythm Club Orchestra was formed in the late 1990’s in Kansas City, by Michael Lande who transcribed many of their arrangements directly from old 78 records of original recordings made in the late 20’s and early 30’s.

Read more about the band and CD at AllMusic.com.

Drums, Percussion, Vocals, Arranged By – Michael Lande

Banjo, Guitar – Steve Swanson (5)

Piano, Celesta – Bram Wijnands (2)

Soprano Saxophone, Alto Saxophone, Clarinet, Flute – Greg Briggs

Soprano Saxophone, Alto Saxophone, Baritone Saxophone, Bass Saxophone, Clarinet – Mark Cohick

Soprano Saxophone, Tenor Saxophone – Marshall DeMynck, Steve Patke

Trombone – Stephanie Cox

Cornet – Barry Springer

Trumpet – Jay Sollenberger

Tuba – Paul Rodabaugh

Viola – Jorge Gutierrez (2) (tracks: 8, 12, 13, 18)

Violin – Marc Abelson (tracks: 8, 12, 13, 18), Peter Knupfer (tracks: 8, 12, 13, 18)

Xylophone – Mark Lowry (6) (tracks: 13)

Stomp Off producer Bob Erdos sometimes taps the shoulder of this particular annotator when he has an album in production by a repertory jazz band. That expression – “repertory jazz” has taken on broad associations, but we mainly mean by it that a band has selected tunes associated with a specific historic jazz ensemble, or some major identifiable style in early Jazz discography. In several respects, the Rhythm Club Orchestra is a throwback to one of the earliest conceptions of repertory jazz – namely, a faithful rendering of transcriptions from original recordings. Most albums on Stomp Off by repertory jazz bands tend to settle upon one performer or ensemble as a theme or stylistic point of reference. But, as Bob acknowledged while reading its titles to me over the phono, this Rhythm Club Orchestra collection seemed to be all over tho musical map. “Maybe the story here,” | mused to Bob, already imagining the line In type, and enamored with my own cleverness, “is that there is no story|”

As it turns out, this seeming non-story turns out to be a fragment of a very real story. Granted, the Rhythm Club Orchestra has not focused upon one towering for obscure) performer or ensemble. Instead, there is a much grander, if unpremeditated, theme that joins much of this music together. Following his bliss in his selection of tunes, leader Michael Lande inclines to hot dance and pop material. The Rhythm Club Orchestra valuably reminds us that the bands and orchestras of the 1920s and 1930s – no matter the hue of the musicians or the venues in which they played – provided music for dancing and for the pleasure of their audiences. Most of the popular music of the era was colorblind and reflexively showbiz. Reflecting this, the titles played by the Rhythm Club Orchestra take in a much broader choice of sources and a more expansive musical reach. While recordings by both white and black orchestras are represented here, several of the selections from the latter would not be characterized to be the “blackest” of their discography. To put it simply, there is more of the chorus line in the music of the Rhythm Club Orchestra than the blues of the cotton fields

But, like the “non-story,” this design was not by design; the Rhythm Club Orchestra was something of an evolving accident. Around the time of his graduation, Michael Lande’s grandfather lent him a record by the Pasadena Roof Orchestra. Michael liked the record well enough, but it was no conversion experience; according to Michael, the reason why he bought a collection shortly thereafter by the McKinney’s Cotton Pickers was because “the cover looked interesting.” Michael was working in a Berkeley record store, and occasionally turning his wages back in for a reissue of Ellington, Bennie Moten, or Jean Goldkette. But still, no epiphany.

The oracle was the San Francisco Starlight Orchestra (whose work may be sampled on Stomp Off). Attracted to their sound and repertoire when he first heard them in 1994, Michael wrote a couple of original tunes “in the style of” for the SSO, but was unhappy with what he had crafted out of whole cloth. Next, Michael transcribed a couple of tunes he liked from the handful of jazz reissues he had acquired. He was curious to hear what those numbers would sound like performed “live” by an orchestra of the caliber of the S S O . Lande decided that transcribing original recordings was not only a useful service, but also more his metier.

His wife’s academic program took Michael to Kansas City not long after. Unable to persuade the SFSO to make the move with them, Michael – if he was to hear more of his transcriptions knew he would have to form a 1920s-sounding orchestra of his own. Without much dragooning, Michael assembled a group and began churning out a couple of transcriptions each month for the band’s rehearsals. Oddly – and in a departure from the obsessed amateurs we normally encounter – the members of what came to be the Rhythm Club Orchestra were all skilled professional musicians. But none were active practitioners of early Jazz and dance styles. (Which may explain why they are able to support themselves at their craft!)

At one point, Michael Lande may have harbored the fantasy we’ve almost all had: Of standing resplendent before an orchestra in crisp tails (or poured into something eye-catching if it is Ina Rae Hutton whom we fancy to be), conducting and cavorting in a manner that is conspicuously entertaining without looking dorkish to audience or musicians. But, Michael decided, the songs carried themselves. When he could not achieve the effect he desired any other way, he wound up seating himself at the drums. Same with the vocals. Thus, a guy who hardly fancied himself a singer or drummer – much less an orchestra leader – became all three. To paraphrase Shakespeare, Michael Lande neither chose greatness nor had it thrust upon him. He backed into it.

When Duke Ellington first heard the derby-sporting, cigar-smoking Harlem pianist Willie “The Lion” Smith, at the Capitol Palace in 1925, he observed that “everybody seemed to be doing whatever they were doing in the tempo The Lion’s group was laying down. The walls and furniture seemed to lean understandingly… the waiters served in that tempo; everybody who had to walk in, out, or around the place walked with a beat.” The Rhythm Club Orchestra comes out of the box displaying its musical temperament with Keep Your Temper, a jives hot dance number written by The Lion that same year. The Lion recorded the number with a pickup band, the Gulf Coast Seven. The Rhythm Club Orchestra models its performance after a 1930 record by the Duke Ellington band, masquerading on Brunswick as the Jungle Band.

Inexplicably, the Ellington record carried the title of the “Cotton Club Stomp,” a title with a wholly different melody when Ellington recorded it in 1929. As the Duke and the Lion were on the best of terms, the misrepresentation was probably an error; certainly it was not by Ellington’s design. In any event, “Keep Your Temper” has a floor-show sort of melody and pulse.

Also included here are two dance line numbers that the Ellington band played at the Cotton Club, Doin’ the Voom Voom, and the Jubilee Stomp. The “Jubilee Stomp” is one of Ellington variations on the “Tiger Rag,” and one of the most effective of his early arrangements.

There’s another Ellington connection to the performance of Cole Porter’s What Is This Thing Called Love? Following his departure from the Ellington band, cornetist Bubber Miley led his own group, furnished accompaniment to some of the dances of Roger Pryor Dodge, and was featured for a time with the Leo Reisman Orchestra. Reisman’s Orchestra played at the Central Park Casino in New York and is noted for helping to launch its pianist, Eddy Duchin.

Seventh Avenue was described by one novelist as Harlem’s “most representative avenue, capturing both Harlem’s “sordid chaos and rhythmic splendor.” There, at 22941/2 Seventh Avenue, was Small’s Paradise, billed as the “Hottest Spot in Harlem,” and there resided the Charlie Johnson Orchestra. Small’s Paradise catered a bit more to the black trade; John Hammond observed that the gals in Small’s chorus line were generally of a blacker hue, while the chorus line at clubs targeting the white trade featured lighter-skinned blacks, or “high yallers.” That Johnson’s Orchestra recorded The Boy in the Boat, the title of which refers to an article of the female genitalia, may reflect the Paradise’s earthier spirit. Though the anatomical reference is midway, the music is lowdown.

Though another New York mainstay, Fletcher Henderson’s band was in something of a trough in 1932 when it recorded Take Me Away from the River, written by Kay Lois Parker, a singer who appeared at Connie’s Inn. The song isn’t exactly high art, but Lande was drawn to it by its “wailing” quality, “those crazy sirens,” and the scoring for the clarinets. The netherworld textures of “Take Me Away From the River” and its subtitle (“Song of the Viper”) suggest the cocaine-ridden Minnie the Moocher and Smokey Joe atmosphere created earlier by Cab Calloway.

Too Late is an example of the way even Joe “King” Oliver, a trumpeter out of the New Orleans ensemble tradition, was adapting to the conventions of orchestrated jazz dance music. By the late 1920s, Oliver had already begun to be plagued with *gum disease and his best days were behind him. However, in the summer of 1929, assisted by a young trumpeter from Chicago named Dave Nelson, Oliver assembled a working band, and shared the horn solos with Nelson. Don Frye, the pianist present when Oliver and the band recorded “Too Late” for Victor Records in October 1929, recalled that Oliver labored over his solos for this title despite pain that had the trumpeter on the verge of tears .This piece has been described as a “robust” blues. Like so many of the selections played by the Rhythm Club Orchestra, it’s eminently danceable, too.

By his own admission, Lande is drawn to the territorial bands, and he shows no geographic prejudice. The black orchestral style that came out of Kansas City and the Southwest was flavored by ragtime and blues, and a propulsive rhythmic drive. Pianist Bennie Moten’s band furnished its own Tin Pan Alley-sounding melodies. Baby Dear, jointly written by Moten with his longtime trombonist Thamon Hayes (who shares credit with Moten for the better known “South”), was recorded by the band twice for Okeh in 1924, and then in 1927 for Victor. Hayes was also Moten’s collaborator on That Certain Motion, which was given a somewhat tongue-in-cheek opening. Titles like this from the Moten repertoire rollick, but not heavy-handedly.

Moten hired William “Count” Basie in 1929 to assume the piano chair, and Rumba Negro, from Basie’s first session with the band, was, despite its description as a “Spanish Stomp,” a typical Moten rebottling of old wine. But, it’s a vintage most of us would be happy to have tableside every night.

While Don Redman was the musical director and fronted McKinney’s Cotton Pickers when that band recorded the four titles from its discography included here, three reflect the hand of trumpeter and arranger John Nesbitt, who crafted some of the Cotton Pickers’ most durable music. Elaborating upon Redman’s example, Nesbitt spiked his tempos and devised his own distinctive rhythmic figures (including the use of staccato repeated notes) and came up with an unorthodox division of labor between the sections of the orchestra. Less drawn to the traditional call-and-response, Nesbitt raised the temperature of his charts by scoring and assigning shorter passages to alternate sections of the orchestra. Crying and Sighing and Stop Kidding epitomize why McKinney’s Cotton Pickers continues to be regarded as one of the slickest of the black bands. Not only did the band have a highly individual sound, its repertoire was based less upon the blues than other black territory bands. Nesbitt’s numbers in particular have an extraordinarily bright and happy personality – which may explain l’II Make Fun for You. Michael Lande has quite an ear; he sings the lyric as disarmingly as did George Thomas on the original in 1930. And be sure to listen to the adaptation from McKinney’s of Some Sweet Day with that great alto sax coda. It sounds as if it were like the stray hair so charged from a vigorous combing that it just can’t be settled down.

Gunther Schuller has argued that Nesbit influenced arranger Gene Gifford of the Casa Loma Orchestra. Gifford made use of the musical and rhythmic figures found in Nesbitt’s work, applying them, perhaps, with too much paint upon his brush. White Jazz has all the hallmarks of the agitated sound, furious tempo, riff-driven flair and agitation that the first generation of jazz critics found tiresome in Gifford’s work. The Rhythm Club Orchestra handles it nimbly as distilled by British bandleader Lew Stone’s orchestra when it was resident at London’s fashionable Monseigneur Restaurant. Stone’s late 1933 recording of “White Jazz” prominently featured the tight drumming and crisp cymbals of percussionist Bill Harty, which is all the model Michael Lande needs to make his “White Jazz” white-hot.

Bandleader Joe Loss – whose treatment of Sentimental Gentleman From Georgia the Rhythm club Orchestra has borrowed reached his greatest popularity during World War I. He once observed that “the better the restaurant or hotel the lower the standard of dancing,” noting that his band was “the band for dancers” among the “young workers” who cared about dance.

It’s probably a stretch to suggest that the British dance bands constitute “territorial” bands; for some of the purists on Stomp Off’s domestic mailing list, Jack Hylton and Billy Cotton might just as well inhabit another planet. Perhaps the renderings here by the Rhythm club Orchestra will dispel some of that myopia. Bandleader and impresario Jack Hylton was perhaps the most prominent of British bandleaders (with the exception perhaps of Ray Noble). The late Albert McCarthy once wrote that the parallels to be drawn between Hylton in England and Paul Whiteman in the United States “need no stressing,” in that both leaders played a variety of music and had an informed sense about jazz. Hylton once divulged that he had American dance band scores sent to him weekly. He studied them carefully, he said, to modify them to the “British temperament.” Let it be said that Hylton made plenty of records that have appeal to the American temperament. Limehouse Blues was probably arranged for Hylton by Leo Vauchant, who had come to Hylton from Lud Gluskin’s Orchestra, a band that admired Bill Challis’ arrangements for Jean Goldkette and Paul Whiteman. Hylton’s recording of “Limehouse Blues,” on which the Rhythm Club models its own, has that hot, but literate-sounding Challis quality. Billy Ternent was Hylton’s chief arranger; his Black and Blue Rhythm was doubtless inspired partly by Duke Ellington’s visit to England in 1933. In fact, the tour was arranged by Hylton.

The Piccadilly Revels, in situ at the Piccadilly Hotel in London, inspire the version of Buffalo Rhythm heard here. Even here there is a nAmerican influence. The Revelers were led by Massachusetts-born pianist Ray Starita, whose brothers Al and Rudy were also active in London dance band circles. “Buffalo Rhythm” co-composer Hyman Arluck was to become better known as HaroldArlen. Marvin Smolev is believed to have been a band contractor and possibly the musical director of Grey Gull Records.

The Rhythm Club Orchestra was augmented with strings for I’d Rather Cry Over You, a song arranged for the Paul Whiteman Orchestra by the aforementioned Bill Challis. Challis’ intuition for balancing sentimentality with a hot jazz feeling, and his distinctive way of voicing Tin Pan Alley harmonies, lend this music a quality that can only be described as having a sweetness that also aches. It loses none of this in the translation by the Rhythm Club Orchestra. Whiteman deployed six singers on the original record- Jack Fulton, Charles Gaylord, and Austin Young on the verse, and Bing Crosby, Harry Barris and Al Rinker (the Paul Whiteman Rhythm Boys) on the refrain. So we can say here that Michael Lande does the work of six men. Thanks to overdubbing, he literally does the work of three in the vocal trio to Jack Yellen and Milton Ager’s Happy Feet, one of the major songs included in the 1930 film revue headed up by Whiteman, “The King of Jazz,” elaborately staged by John Murray Anderson.

Gold Digger, which the Rhythm Club learned from an original stock orchestration, is undeservedly obscure and something of a surprise. A 1927 blurb in Metronome, unearthed by Ellington scholar Mark Tucker, reports that Duke Yellington [sic] and Will Donaldson had written the song some years earlier, but had not been able to interest a publisher. There is circumstantial evidence that Donaldson may have helped to write one of Ellington’s earliest orchestral recordings – “Rainy Nights” – so a collaboration between the two seems probable. Tucker identifies a version of “Gold Digger” by Johnny Ringer and his Rosemont Ballroom Orchestra on Gennett. More recently, another version has surfaced that was recorded for Edison by Joe Herlihy’s Orchestra in the summer of 1927, but not released at the time (it can be heard on Biograph BCD 129). “Gold Digger” is another engaging number that conjures up a line of high-kicking legs. The Rhythm Club Orchestra appears to be playing from the same stock orchestration as Herlihy. Rest assured that after opening at the Cotton Club in December 1927, Ellington’s name would thenceforth be spelled correctly.

The body of recordings made by Red Nichols, Miff Mole and their associates in the 1920s were dismissed or overlooked by early jazz critics. They thought the music of Nichols and his associates was lacking in testosterone and was too far removed from the core suffering blues to be considered coin of the realm. Some of the music may stagger a bit under the weight of its complexity, but it’s often immensely innovative and daring. Fud Livingston’s Imagination, a thoughtful number with a hint of a smile to it, has the gossamer quality that some found so objectionably un-jazzy. Frank Driggs and Richard DuPage once observed that this music was “youthful and exuberant and… stood for their mutual pleasure as musicians, and for those of the public who understood them.”

Something similar could be said of Michael Lande and the Rhythm Club Orchestra. Lande explains that he made these transcriptions and assembled this orchestra for the sheer pleasure of it. He never calculated upon seeing his name on a theater marquee, much less enshrined in the catalogue of Stomp Off Records. This edition of the Rhythm Club Orchestra continues to perform in Kansas City to great public favor.

However, since recording the album, Michael and his wife have returned to northern California. For a second time, Michael Lande has had to move and leave an orchestra behind. This time his own! Lande may assemble a new Rhythm Club Orchestra. Then again, he says, he may not. Which is a sad prospect for those of us who would look forward to hearing more from a Rhythm Club Orchestra, nourished with fresh transcriptions from Michael, not to mention his ingratiating vocals and authentic touch at the traps.

Instead, Michael could turn out like a number of territory bandleaders who came before the recording horns and microphones only once. Which may explain why, as I sit here listening to the Rhythm Club Orchestra and tapping my feet exuberantly, my head shakes mournfully. And that, ladies and gentlemen, is the story.

Rob Bamberger

October 1997

Rob Bamberger is the host of the long-running HOT JAZZ SATURDAY NIGHT, heard weekly on public radio WAMU-FM (88.5) in Washington, D.C., and distributed internationally by National Public Radio and Public Radio International on America One and the Armed Forces Radio Network.